THE METROPOLITAN OPERA (2011)

John Adams (Composer, Conductor)

Alice Goodman (Librettist)

Featuring

James Maddalena (Richard Nixon), Janis Kelly (Pat Nixon), Robert Brubaker (Mao Tse-tung), Richard Paul Fink (Henry Kissinger), Russell Braun (Chou en-lai), Kathleen Kim (Chiang Ch’ing), Ginger Costa Jackson (First Secretary to Mao), Teresa S. Herold (Second Secretary to Mao), Tamara Mumford (Third Secretary to Mao), Mark Grey (Sound Designer)

Today I clicked on the little heart that bought up my wish list on The Metropolitan Opera’s streaming app, and decided it was time to experience the John Adams opera Nixon in China.

When I became aware of this work many years ago, my first thought was: What kind of person would pay to sit through an opera about Richard Nixon? Yuk.

But I was a mere puppy then, and now that my knowledge of opera is more well-rounded I realized that the 1972 hands-across-the-water summit between the United Stated and China is a worthy subject matter for opera, and from that I’ve been looking forward to seeing it.

To choose which rendition to view for the first time, I was torn between this not-quite-silver anniversary version from The Metropolitan Opera and a 2012 production I’ve bookmarked from the Theátre du Châtelet in Paris. While I was intrigued by what a company from Paris might make of this slice of American internationalism, I opted for the earlier New York version as it starred James Maddalena, the baritone who created the definitive Nixon for this work.

Nixon In China was composer John Adams’ first opera. His librettist was Alice Goodman, who was at that time another opera neophyte. They created a sensation with this work, which has seen consistent productions staged around the world over the last 35 years.

THE OPERA

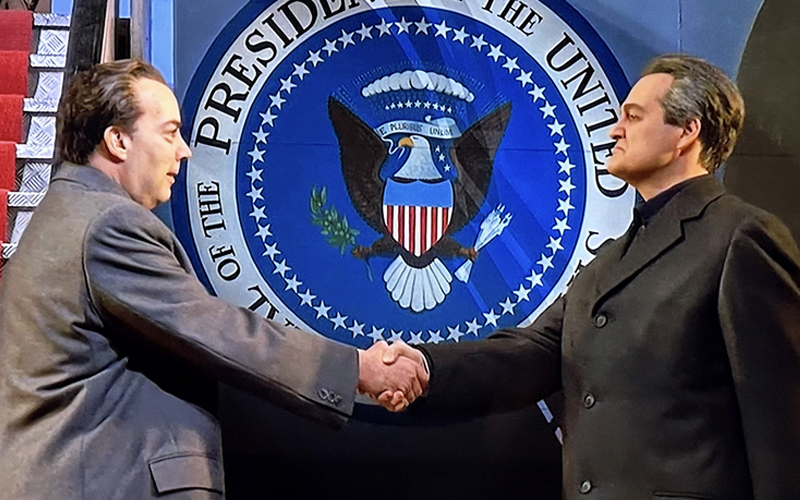

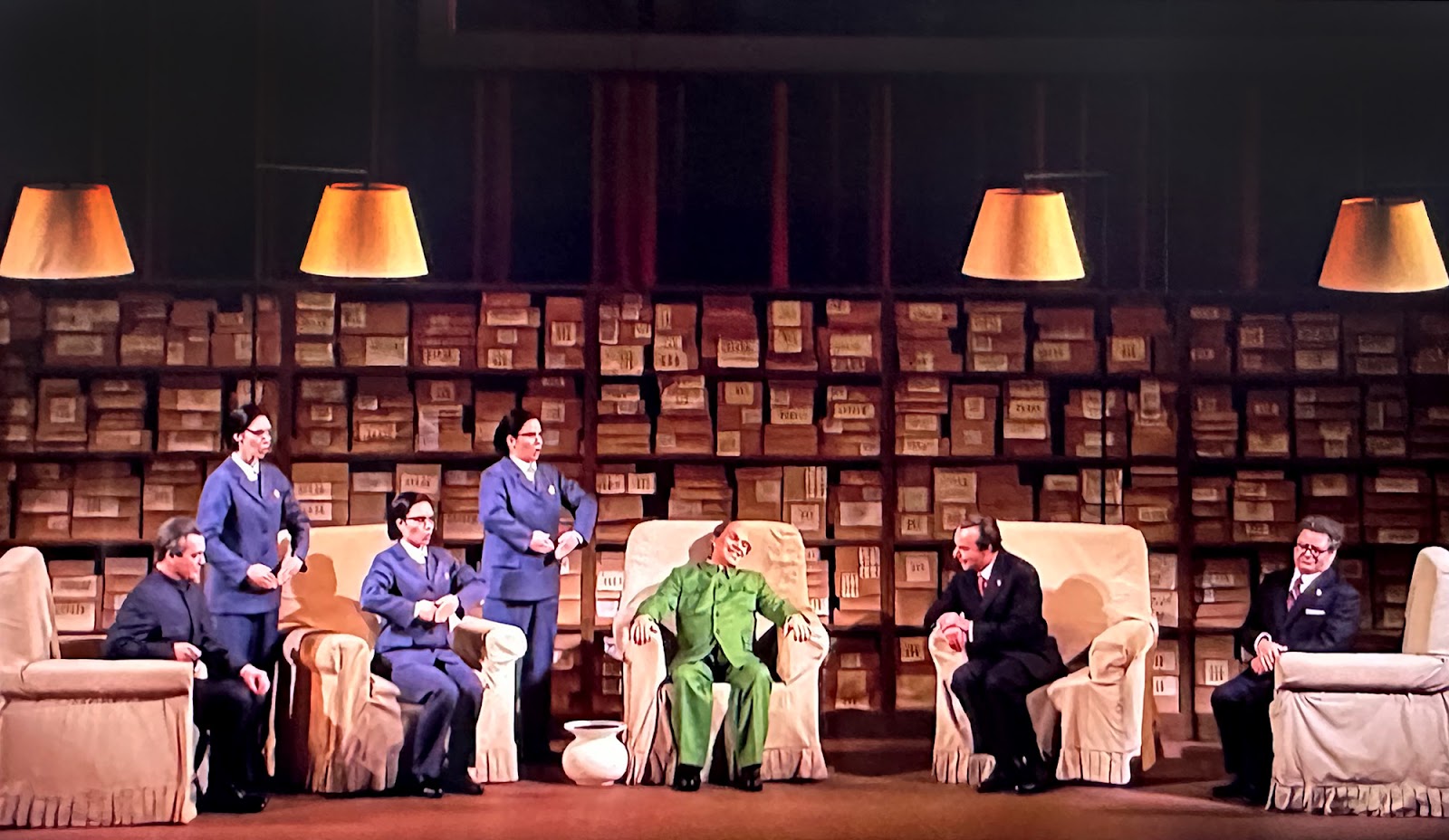

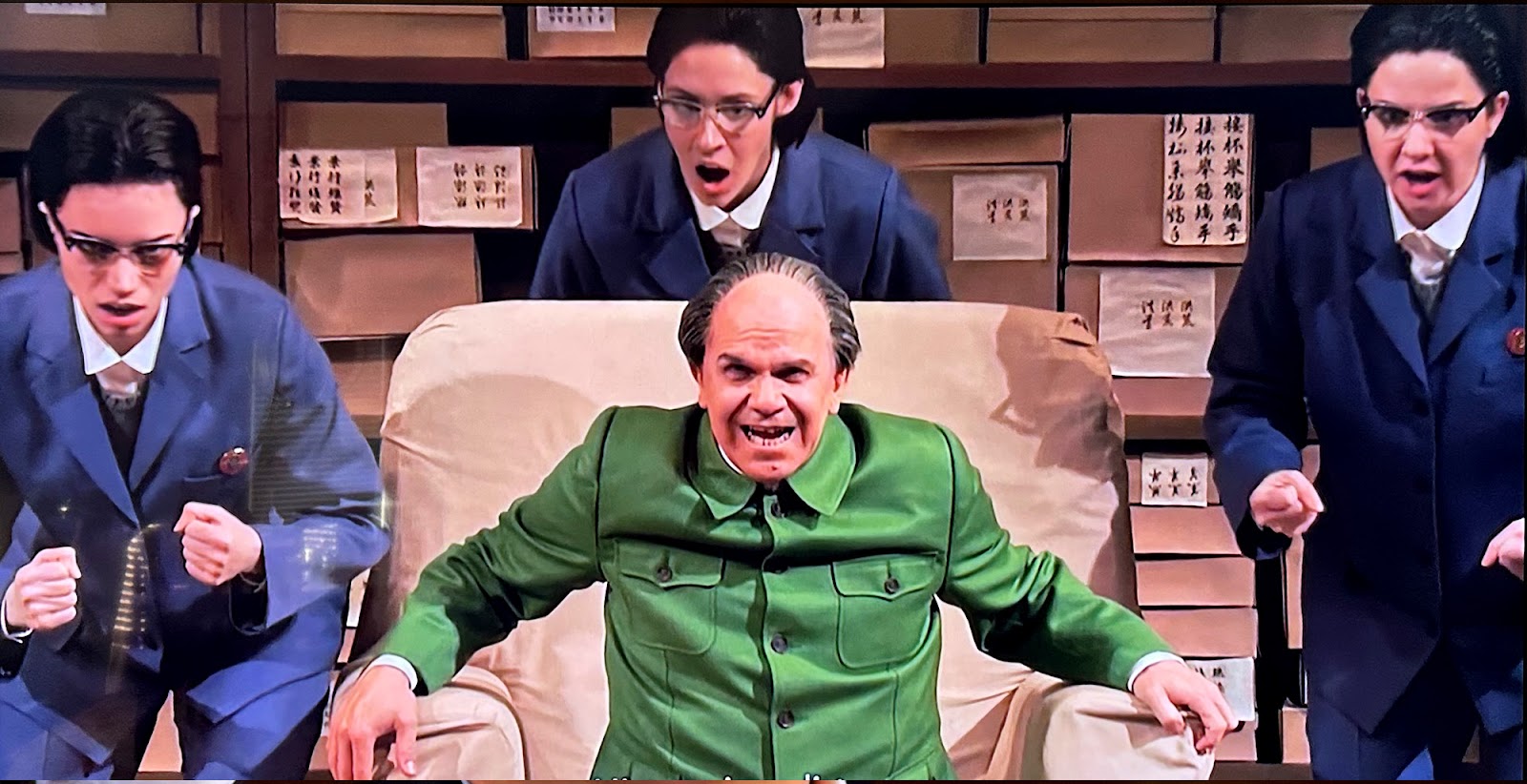

In the opening act, a repetitious string arpeggio over contrasting slabs of woods underscores a choral prelude featuring a panorama of Chinese society circa 1972. Nixon and the diplomatic corps arrive on Air Force One. This sequence and everything that follows in Act I – with Nixon, Mao, Kissinger and Zhou Enlai meeting in Mao’s apartment – basically adheres to historical fact. The American president is roused from a nap for an audience with Mao on a stage set that is a ringer for the real deal – four chairs with putty-colored dust covers in front of an immense wall of books and archival boxes. There the four leaders talk in a disjointed cadence, with Nixon and Kissinger wanting to discuss realpolitik, Mao philosophizing in a spacey, congenial mood, and Cho En-Lai interjecting to try and keep the Chinese agenda on track.

You don’t have to know your 20th century American history to figure out that the words spouted by the characters are a mashup from a transcript of the actual proceedings. It’s not possible for a libretto this geeky to have come from the imagination of a mere wordsmith. From the jump we realize that with their freshman effort Adams and Goodman were not exactly on a mission to reinvent bel canto opera.

Act II begins with loosely factual vignettes of Pat Nixon’s goodwill mission activities. After this episode the attachment to historical fact is dispensed with; in the scene that follows, we get a load of hokum which plays out like this:

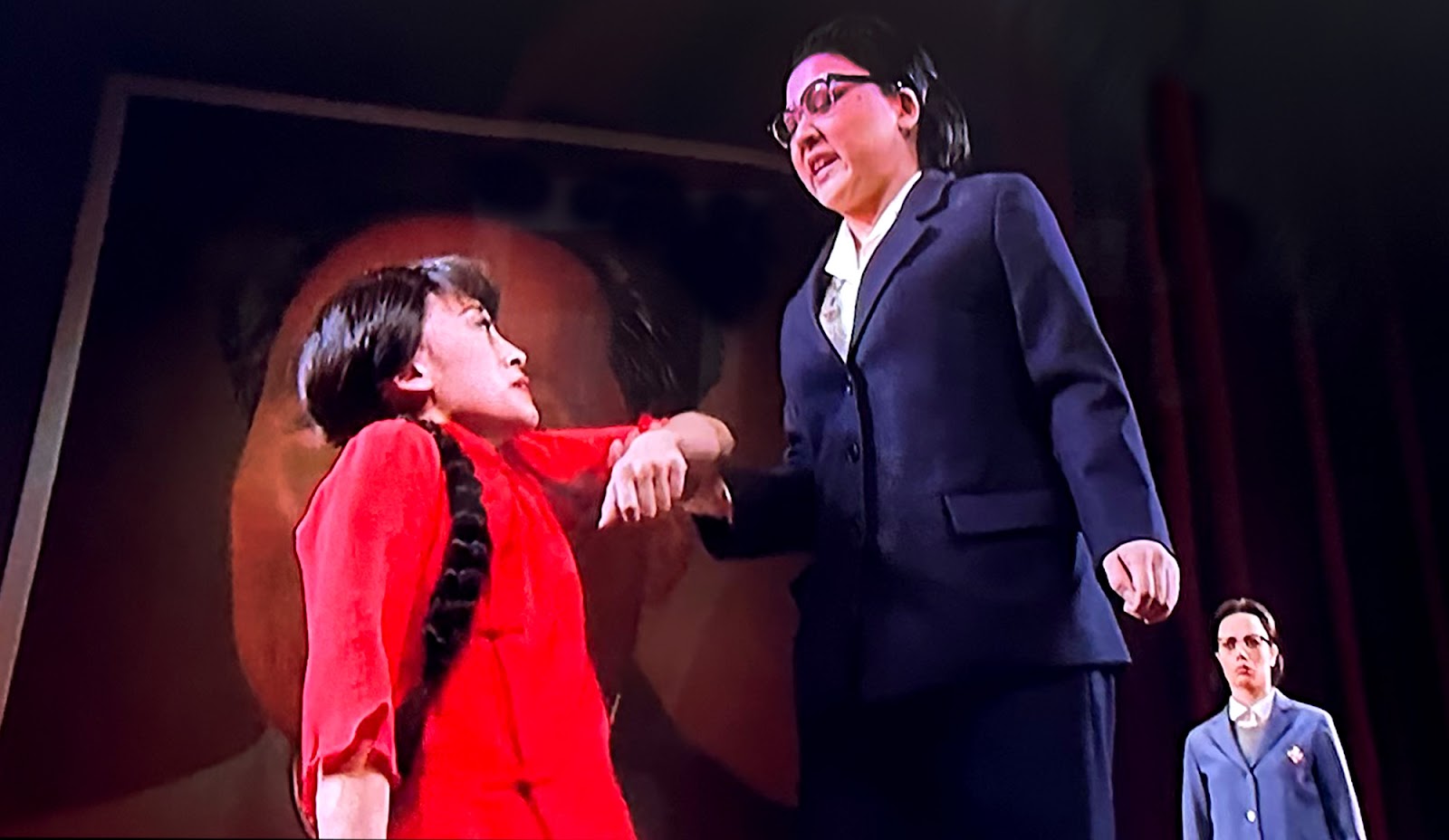

The President, his wife and other dignitaries attend a performance of Chinese opera. It starts reasonably enough before descending into chaos with the Kissinger singer (Richard Paul Fink) assuming a second role as a capitalist villain who molests a Chinese working girl while she’s tied to a stake. When the Nixons arise from their seats to try and help the girl everything gets nutty with Madame Mao (Chiang Ch’ing) shrieking at the top of her register about how you can’t mess with her because she is the wife of Mao Tse-Tung while actors pantomime Red Guard executions beneath a huge poster of Mao.

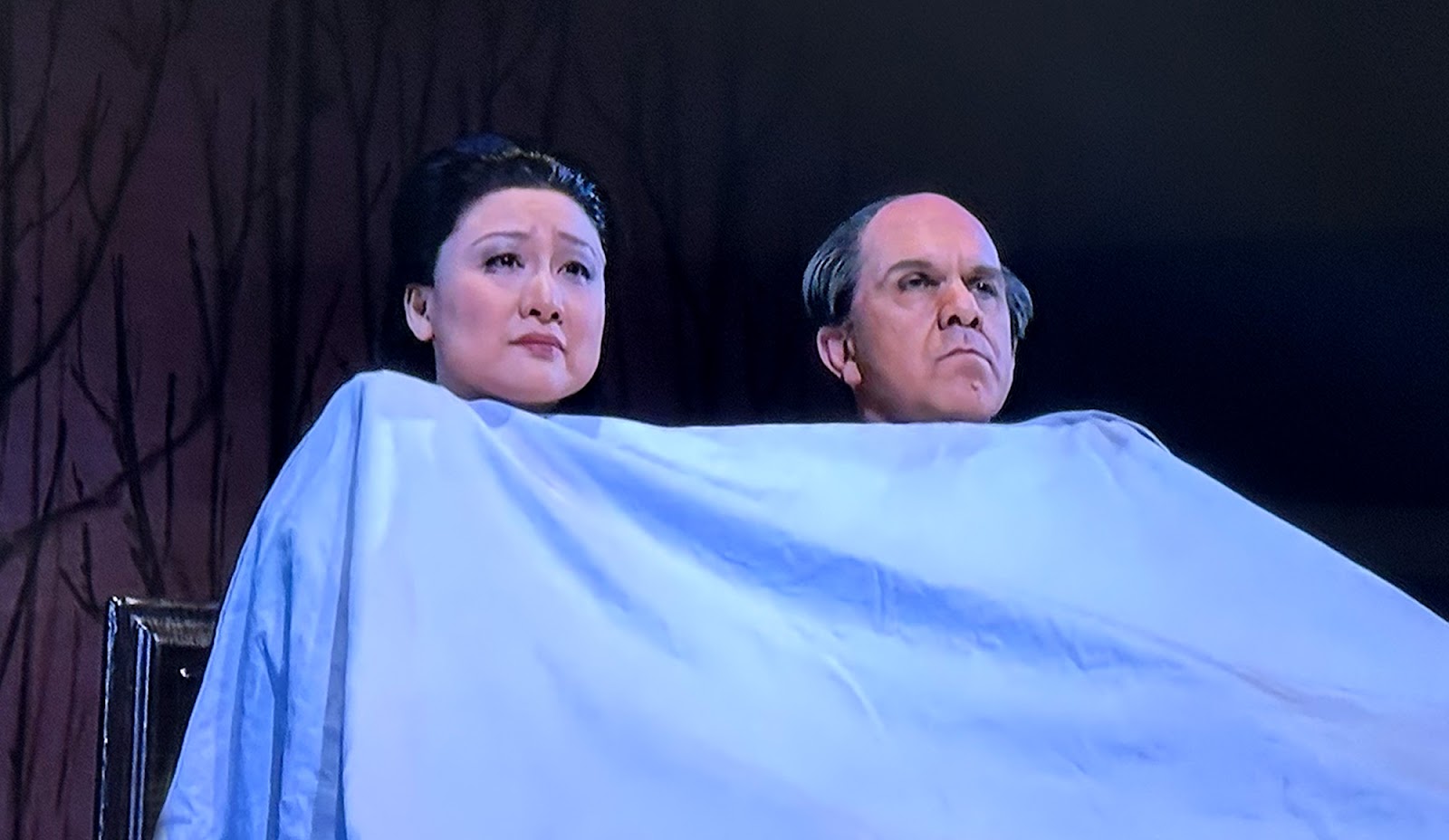

In Act III we get more tepid surrealism with the lead characters all clothed in jammies occupying the same theoretical bedroom offering soliloquies in multipart harmony. By the end of the opera I was far along the critical road less travelled and disagreeing with the critics who give this opera raves; the second half of this thing had me dully staring at the screen lamenting how a promising operatic subject could so easily get derailed in development by a misguided hippy-dippy vendetta against the mid-century American conservative order and doom Nixon In China to being both questionable entertainment and crummy art.

Oddly, I found that as the plot got more insipid in the second and third acts, the music – in particular the vocal writing – got better. There was more urgent power in the music and both the verbiage and melodies of the vocal lines were tighter. But though I felt the words improved after the opening act, that’s only relative. The libretto in its entirety has no soul, no lyricism, no flow. I carp about this often in opera, but I say there needs to be a priority on verve and swing and rhythm in any kind of music. It’s a curious problem here because the music of Nixon in China does have quite a steady pulse throughout, so it’s a mystery as to why Adams’ wordsmith Goodman didn’t play off of it.

THE PRODUCTION

Act I begins with a big chorus garbed in different personas of the Chinese society circa 1972 singing inspirational slogans. It stood out to me that The Met outfitted a lotta honkies in those Red Chinese outfits! If this was staged today there would be a chorus line of progressive activists howling for the head of the Met’s artistic director in the name of ethnic purity (or, as some might say, ethnic cleansing) to put more Asians in the production.

While I think it would be cool to have an all-Asian chorus, reality dictates that it might be a casting nightmare to locate and engage 100 Asian singers who all hold Opera Performance MAs who are seething with the same exact thought:

“I can’t believe I’m standing here in the middle of an anonymous mob in a goofy fur hat with a red star on it for only 6 minutes stage time. If there were any justice in the world I’d be in Santa Fe right now rehearsing for the lead in Traviata. At this rate I won’t even cover the fucking interest on the student loan.”

James Maddalena is to the role of Nixon in this work as Jon Vickers was to Peter Grimes. He simply is the man you have to contact if you are staging this work. Maddalena certainly has the commanding voice for it, and he has Nixon’s mannerisms absolutely down: the licking of lips, the abrupt furtive glances, and that special smile so often seen on the face of our former president that resembled not so much a man in good humor but the toothy glee of a rabid opossum as it advances upon a dumpster of opportunity.

To assist in Maddalena’s characterization, the makeup department thoughtfully put some lip gloss or vaseline on Maddalena’s upper lip to replicate the sweat that was ever-present on the real Nixon whenever he was under duress or subjected to the glare of press conference cameras. Or maybe Maddalena — whose performance in this work, after many well-crafted iterations, is so impeccable — has assumed the role so completely that he has really learned to sweat like Nixon on cue!

In the opening scenes I had a thought that the vocal range of Nixon should have been scored lower to evoke the real man’s brooding, self-pitying baritone; but if Adams had channeled Nixon’s soul through the main character’s vocal range he might have ended up with something prohibitively murky like Bluebeard’s Castle and blown his commission.

Janis Kelly as Pat Nixon makes a prefect bookend to Maddalena’s rendition of her husband with a spot-on replica of the former First Lady. I was surprised to find she is British, as she played the part of a plasticine Barbie doll political trophy wife like a true red, white and blue American. Fine voice too. Richard Paul Fink‘s Kissinger was another good casting, playing the former Secretary of State with appropriately wily, pissy, and power-mad edge.

Robert Brubaker‘s Mao Zedong is a little more problematic. Not for his voice, which was fine; I just found it a little disconcerting to see a caucasian playing Mao. I also thought the physical infirmities of the then-aging Premier as played by Brubaker were a little heavy-handed, but I suspect that’s more the gawky literalism in Peter Sellars‘ direction than the actor’s decision.

And I have to say – that was one creepy hairpiece he had on! When it comes to creating suspension of disbelief, opera viewed as streaming media is one tough customer. What works wonderfully for the audience in the seats is somewhat more exposed when viewed in closeup. Everyone has artificial hair and those sprit gum lines aren’t subtle. (I can’t even imagine the wig budget for this production – even the Asian cast members wore them). Magnified on film we get to see all the prop masters little tricks: The aperitif glasses of baijiu filled with crimson resin (imagine the stage manager’s nightmare having interns running around filling all those little things with liquid!). The way Mao’s Zhongshan suit hangs awkwardly on Robert Brubaker from being made of polyester instead of good old tough Communist Chinese twill. And all that foundation – pancake, pancake, and more pancake!

For those of you who dream of a career in opera production, watching these productions via The Met’s streaming app is a good intro to show you the things you can get away with when you’re 10 yards away and 6 feet above a live audience.

SUMMARY

As we move into the future of this medium, will the opera Nixon in China be regarded as a grand statement or historical knickknack? To answer I have to return to my original question: What kind of person would pay to sit through an opera starring Richard Nixon and Chairman Mao?

I still don’t know. Nixon In China is maddeningly uneven – an inspired theme of modern history with some great interpreters, but with a plot that is stilted and unpoetic in the first half, then loaded with heavy-handed allegory the rest of the way. There is good orchestral music writing throughout which helped me hang in there.

Despite its merits and flaws, through whatever artistic or academic or intellectual prism you may view Nixon In China, it’s still an opera about two weird, paranoid, and deeply flawed men who you would dread the prospect of having to be trapped in the same room with. So I can’t imagine I’ll ever pay a load of money to spend three hours with their dramatic doppelgängers.

Oh well. Henry Kissinger‘s former aide Winston Lord has gone on record to say he adores Nixon In China because it is very detailed in its authenticity, the Act I dialogue being “almost verbatim” compared with what actually happened. So I guess some people think this libretto is cool. If the day comes when you find yourself with a load of State Department factotums couch surfing at your place and you’re looking for something for them to do so you can get them out of the house to change the sheets and clean the bathroom, Nixon In China might just be their ticket.

“Works of art which lack artistic quality have no force, however progressive they are politically. Therefore, we oppose both works of art with a wrong political viewpoint and the tendency towards the “poster and slogan style” which is correct in political viewpoint but lacking in artistic power.” (Mao Zedong, ‘Quotations From The Chairman’, 1957)